Interacting with subjects in the wild is what I love most about photography. Even though I’ve been shooting macro for years, I’m always discovering exciting things about the natural world with each photo I make. I love learning about different species, figuring out the best way to approach them, and capitalizing upon fleeting opportunities. But before I can do any of that, I need to find them. There are never any guarantees, but I do have a few tips and tricks to maximize chances. Prior to heading into the field to work with live subjects, it’s important to learn about your gear and practice to build your confidence. If you’re shooting with the M.Zuiko 60mm F2.8 Macro, be sure to check out my article on mastering the 60mm Macro. Once you’ve gotten your head around the equipment, it’s time to game-plan.

Determining a game-plan may seem obvious: Spend some time in the field, find little critters, and make awesome photos – but a little planning can make a huge difference. Don’t get me wrong, I do plenty of freestyling when I just take my camera into the yard to see what I can find. An entire day dedicated to macro, on the other hand, is a whole different story.

Location, Location, Location

If you want to photograph bugs, go to a place with lots of bugs! Look for wetlands, meadows, or other areas with varied vegetation that are known to attract insects. Any area of dense plant life is going to yield a high volume of opportunities. Add a body of water to the scene, and you’re bound to find even more. Insects such as dragonflies, damselflies, and mayflies lay their eggs in water and spend a lot of their time cruising the fields nearby.

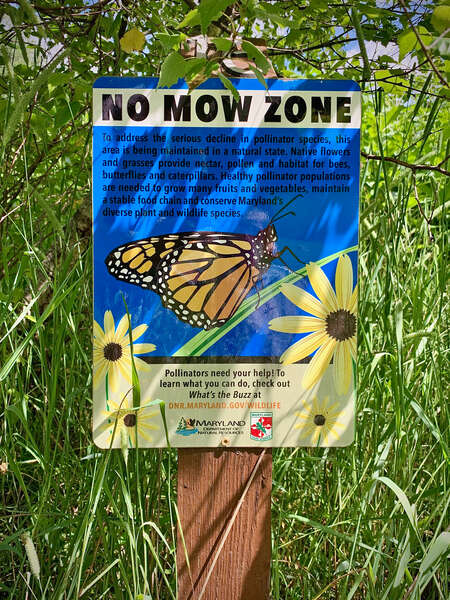

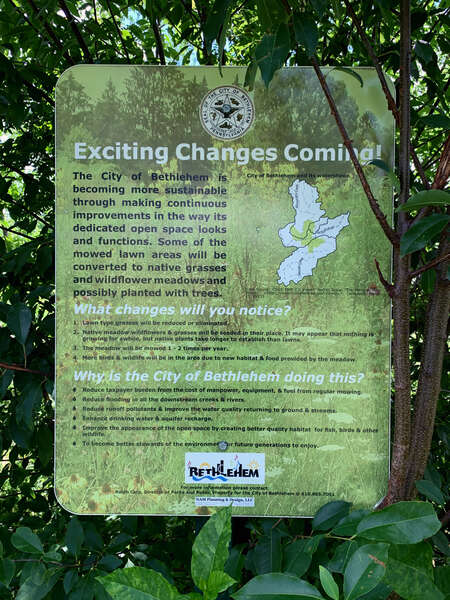

If you’re looking for a particularly diverse population of tiny wildlife, look for areas with diverse vegetation. Botanical gardens, for instance, offer a huge assortment of plants and flowers. That assortment attracts a wide variety of interested insects. Some towns (like mine!) have wildflower or pollinator projects. These projects don’t only maintain areas’ natural landscape, but they also provide excellent macro opportunities. Another way to find macro hotspots is to contact your local parks department. Ask if they know of any areas that might be abuzz (get it?) with insects. Park rangers and naturalists are valuable sources of local wildlife information and can turn you on to amazing spots that you never knew existed!

Timing Matters

Most insects and spiders are ectotherms. This means they require warmth from the sun to warm their bodies which tends to make them more active in the middle of the day—but shooting energetic subjects in the midday sun can be a major challenge. I highly recommend heading into the field as the sun is rising. You’ll encounter much slower subjects and should have a much easier time getting them to cooperate. And there’s a bonus benefit—water droplets! When morning dew collects on plants, insects, spiders, and webs, it provides an extra element of interest for your photos. Not only will it look cool, but the added weight of droplets on insects’ wings can make flying difficult. When you find sleepy insects waiting for the sun to dry their wings, you can move in for those close-ups.

If you’re not much of an early riser, you can try sundown. Some critters maintain their body heat into the night and use the cover of darkness to hunt for prey and avoid the animals that prey upon them. Shooting at night will reveal an entirely new set of macro subjects ranging from moths to spiders and a whole bunch of creepy crawlers in between.

Be Patient

Patience is considered a virtue. This is especially true with macro. When you’re able to physically slow your pace and mentally relax, you’ll find more subjects, hold your camera steadier, and—ultimately—produce better images. While it can be tempting to plow through the woods expecting subjects to present themselves to you, that approach rarely works.

I suggest walking slowly while continuously scanning your surroundings. Many arthropods are masters of disguise. As you scan, be on the lookout for movement and any contrasting shapes, colors, or textures. If you take the time to look really closely, you’ll start to pick up on the subtle deviations from the natural environment. For example, a mantis blends in perfectly with the grass or plant stems. If you slow down and really inspect those stems, you’ll notice when something looks just a bit different or begins to move in a not-so-plantlike way.

Slowing down won’t only let you see more, but it can let you hear more, too. That’s right, you can find insects by listening. In fact, it’s probably the easiest way to find grasshoppers. As you quietly move through the meadow, stop and listen for grasshoppers’ chirping and try to determine the direction from which it’s coming. Take a step or two toward the sound and stop again. If you move too quickly, the chirping will stop altogether, but by moving a little at a time, the grasshopper will settle and resume chirping. With enough patience, I can usually pinpoint the exact location and move in for a shot. Give it a try!

Search High and Low (Literally!)

If you’re anything like me, your default gaze will fall at your own eye level. Sure, some subjects might be five feet off the ground, but many arthropods live on trees or in the grass. Physically lowering yourself can help you to find more subjects and help to slow your pace (see above). Once you find a subject, consider an angle that brings the audience into your subject’s world. Most people don’t spend much time crawling around meadows looking for bugs. If/when they do encounter insects, it’s usually from a top-down point of view. When you shoot from the ground, you can provide an altered perspective that brings viewers into your subject’s world. Similarly, looking up can result in otherwise missed opportunities. Spiders, ants, caterpillars, and a whole host of other arthropods can be found on the trunks and branches of trees. Be sure to keep your eyes peeled.

Learn About the Plants

While you don’t need to be a full-blown botanist to find insects in the field, a little plant knowledge can go a long way. Whenever I find a new (new-to-me) insect or spider species, I take note of the vegetation so I can look for more in the future. If I’m targeting a specific type of subject, I’ll research known host plants so I can search for them. It’s usually easier to spot plants than it is to spot itty-bitty creatures. I always know I’m bound to find milkweed beetles on milkweed. I can count on thistle weevils doing their thing on thistle. The list continues as the relationship between insects and plants is essential. The more you pay attention to that relationship, the more subjects you’ll find.

Bring the Bugs to You

For very little money and very little effort, you can bring macro subjects right into your yard! Each spring, I buy a mix of wildflower seeds and plant them in pots and flower boxes around the outside of our house. It’s easy to do, they look nice, the kids love them, and they attract bugs! If you aren’t sure which wildflower seeds to choose, just look for seeds of the flowers that are native to your region. Those plants are the most likely to attract native insects. Growing your own wildflowers provides you with on-demand, on-premises opportunities for shooting and learning.

Give Yourself a Better Shot at Getting Better Shots

By nature, most insects and spiders are uncooperative. If you’re targeting live subjects, a slow, measured approach is a critical component to making a successful photograph. Move little by little and try to establish trust before rushing to the desired working distance. Years in the field have taught me to start a little further back, press the shutter button, move closer, repeat. I call this ‘being okay with getting A SHOT without obsessing over THE SHOT.’ I love 1-to-1, high-magnification macro images just as much as anyone, but scaring away too many subjects can be really frustrating. And you know what? Sometimes those images taken on the way toward 1-to-1 end up being my favorites.

As you approach subjects in the wild, it isn’t uncommon to get only one chance to make your image. The last thing you want to do is realize your settings were wrong after your subject has fled. I recommend testing your exposure before moving toward your subject. While giving your subject a bit of space, focus on a nearby twig, and take a shot or two. Once you’ve confirmed your settings from a safe distance, you can move closer for the real thing. As you get to/near that minimum working distance, be careful to keep your movements subtle to minimize the risk of startling your subject. If you’re fortunate enough to get to your desired position, it’s time to work the shot. Spend some time with the subject and vary your angles, exposure, and focus. You can even use in-camera Focus Bracketing to capture a series of images with varied in-focus regions or in-camera Focus Bracketing to produce an image with a greater perceived depth of field.

Instagram: @innis2winnis

Chris McGinnis is a macro photographer based in Bethlehem, PA. Since 2016, Chris has been getting up close and personal with tiny creatures as he aims to showcase the wonder and beauty of their existence that often go unnoticed.